|

One of the important factors that led to

much of the diversity seen in the art of Neue Sachlichkeit

was demographics. Berlin at the time was the fourth largest city in

the world. But Germany was a country with a number of large cities and

thriving cultural centers. Art was able to develop and flourish

regionally. And as the 1920's progressed, the movement became broad-based.

It included many individual styles and well as local groups. At the same time, the lack of any

single dominant cultural

center, in contrast with Paris for France, at least initially may

have contributed to

a lack of attention and recognition by the art community outside Germany.

Expressionist art

returned within

Germany in the

early Postwar period like an unmanaged garden after a long winter.

Initially a new generation of artists began to pour out work,

benefiting from a recovery in the market. As Expressionism was

supposed to emphasize spiritual values, many of its supporters

became critical of this commercialism . Soon there was a call for a

"new naturalism", and by 1919 the pressures against Expressionism began to build. The result was the abandonment of

the Expressionist and Modernist styles by groups of artists in

various parts of the country. In

contrast with Italy, where there were strong

classical traditions for artists to fall back on, Germany had fewer

indigenous art traditions to build on, once Expressionism was

set aside. Most notable the Germans admired the Nazarenes and

several artists

of the German Romantic movement (i.e., Caspar David Friedrich,

Arnold Boecklin). At the same time, many German artists of this time

also followed developments in Italy, especially through the journal Valori

Plastici, which covered artists in Il

Novecento Italiano and Pittura Metafiscia (Giorgio de Chirico,

Carlo Carra & Giorgio Morandi). It is important to note that there

was a strong affinity between German artists and Italian art, both

classical and contemporary. A chart

showing some influences on various Post-Expressionist artists is

available here. Germany in the

early Postwar period like an unmanaged garden after a long winter.

Initially a new generation of artists began to pour out work,

benefiting from a recovery in the market. As Expressionism was

supposed to emphasize spiritual values, many of its supporters

became critical of this commercialism . Soon there was a call for a

"new naturalism", and by 1919 the pressures against Expressionism began to build. The result was the abandonment of

the Expressionist and Modernist styles by groups of artists in

various parts of the country. In

contrast with Italy, where there were strong

classical traditions for artists to fall back on, Germany had fewer

indigenous art traditions to build on, once Expressionism was

set aside. Most notable the Germans admired the Nazarenes and

several artists

of the German Romantic movement (i.e., Caspar David Friedrich,

Arnold Boecklin). At the same time, many German artists of this time

also followed developments in Italy, especially through the journal Valori

Plastici, which covered artists in Il

Novecento Italiano and Pittura Metafiscia (Giorgio de Chirico,

Carlo Carra & Giorgio Morandi). It is important to note that there

was a strong affinity between German artists and Italian art, both

classical and contemporary. A chart

showing some influences on various Post-Expressionist artists is

available here.

The years 1920-1925 saw the

concurrent development of the core groups of Neue Sachlichkeit art,

in Berlin, Munich, Dresden, Cologne and Hannover. These were years

of economic and political instability. The counter-movement to

Expressionism was fostered by a considerable attention in art

periodicals, variously referred to as Post-Expressionism, or "Neo Realism", or "Neo

Naturalism", or "Magic Realism" or "Magic Naturalism" .

Ultimately, with the opening of Gustav Hartlaub's exhibition in

Hannover during June 1925, under the banner "Die Neue

Sachlichkeit", the movement obtained broad recognition and the name

that would be applied to the movement thereafter.

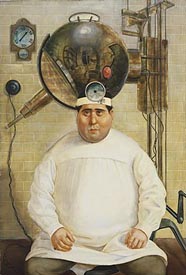

Art critic Emilio Bertonati characterized the art of the Neue Sachlichkeit

by breaking it down into four

groups. Works by individual artists may seem to fall into different groups,

but this chart provides basic categorization.

Protest (socially critical):

Georg Grosz, Rudolf Schlichter,

Otto Dix, Otto Griebel, Barthel

Gilles, Karl Hubbuch, Adolf Uzarski

Geometry (Simplified or constructive):

Heinrich Hoerle, Anton Raderscheidt, Carl

Grossberg

Poetic (or rustic):

Georg Schrimpf, Alexander Kanoldt,

Carlo Mense, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Reinhold Nagale

Magic (naturalistic or detailed):

Christian Schad, Georg Scholz,

Franz Radziwill,

Rudolf Dischinger,

Wilhelm Schnarrenberger, Gert Wollheim,

Grethe Juergens, Franz Lenk

In

these groupings the more typical works of Magic Realism

generally occurred

within the last two groups.

Paintings by Christian Shad and Franz Radziwill are most often cited

by writers, yet Radziwill was slow in moving from Expressionism and

eventually drifted toward Surrealism . Some pieces by Georg Scholz,

Alexander Kanoldt and

Carlo Mense

are representative. The somewhat

cynical work of Rudolf Schlichter and

of Otto Dix in many cases display some

characteristics of Magic Realism .Dix, through his intense study of the old masters, was able

to achieve varied and stunning results as the decade progressed. It was Dix's intense passion for life as expressed in his art that

has left us one of the strongest artistic legacies during this period. generally occurred

within the last two groups.

Paintings by Christian Shad and Franz Radziwill are most often cited

by writers, yet Radziwill was slow in moving from Expressionism and

eventually drifted toward Surrealism . Some pieces by Georg Scholz,

Alexander Kanoldt and

Carlo Mense

are representative. The somewhat

cynical work of Rudolf Schlichter and

of Otto Dix in many cases display some

characteristics of Magic Realism .Dix, through his intense study of the old masters, was able

to achieve varied and stunning results as the decade progressed. It was Dix's intense passion for life as expressed in his art that

has left us one of the strongest artistic legacies during this period.

Two important types

of Magic Realism developed during this period, and both types were

later adapted by artists in other countries. One type was a

dreamlike, even toy-like, miniature style, with its roots in Rousseau

or in

early de Chirico,

filled with mystery or strangeness. Often this approach uses unusual

viewpoints and juxtapositions, or a skewed or restricted palette. Varying

degrees of stylization may be introduced. The second

type was a more

naturalistic style which selectively used highly defined details,

which has multiple points of interest throughout the work. This

type was rooted in the art of the Flemish and German masters, as

well as in contemporary currents in Italy. In addition to style, the

artist's choices of pictorial elements and subject matter contribute

to give a work of Magic Realism the power to mesmerize.

Our

discussion continues as Magic Realism is brought to other countries.

The topics include its development in other European

countries and subsequently its importation in the Americas.

Neue Sachlichkeit Gallery

European Magic

Realism Gallery

American Magic Realism

Gallery

Chapter 1 Magic Realism Introduction

Chapter 2 - Roots of Magic Realism

Chapter 4 - Surrealism vs Magic Realism

Chapter 5 - Magic Realism in other European

countries

Chapter 6 - Magic Realism in the Americas

(1)

Chapter 7 - Magic Realism in the Americas (2)

Chapter 8 - Contemporary Magic Realism

Chapter 9 - The Future of Magic Realism

Email:

dreams@tendreams.org

|